By Zuzana Bednarik, North Central Regional Center for Rural Development

1 Introduction

Rural communities face ongoing challenges related to population decline, labor shortages, and uneven economic opportunities. In recent years, self-employed in-migrants[1] have been viewed as a potential driver of rural revitalization. These individuals contribute to job creation, stimulate local markets, and strengthen rural–urban linkages. However, while their initial impact on rural economies has been well recognized, a critical question remains: do these in-migrants stay long enough for their entrepreneurial activities to generate lasting benefits? The sustainability of rural job creation depends not only on attracting in-migrants with an entrepreneurial path but also on understanding the factors that influence their decision to remain in rural areas over time.

Previous research has examined how in-migrants contribute to rural economies through business formation, local spending, and community engagement. Studies highlight both positive and negative effects on social capital: while frequent movers may invest less in community networks (Hotchkiss, n.d.), entrepreneurial in-migrants can strengthen local ties through collaboration and engagement (Bosworth & Atterton, 2012). Economically, in-migrants have been shown to fill labor market gaps and stimulate new business activities (Kalantaridis, 2010; Eliasson et al., 2014). Broader analyses emphasize rural–urban interdependencies and the diversity of migration patterns that shape local outcomes (Chi & Marcouiller, 2012; Stockdale, 2015).

Despite this growing body of research, little is known about the staying behavior of self-employed in-migrants. That is, whether they plan to stay or move elsewhere. Most studies focus on motivations for moving or initial entrepreneurial outcomes, overlooking the influence of social integration, business success, and community conditions on long-term retention. This gap limits understanding of whether in-migrant entrepreneurship generates enduring economic benefits or merely short-term activity in the rural location where they reside.

This study examines the relationship between the social and economic characteristics of self-employed in-migrants and local entrepreneurs and their intention to stay in their rural communities. Using data from the 4R-Stat Baseline Survey 2024 (Bednarik et al., 2025), a logistic regression analysis was employed to examine the determinants of in-migrant and local entrepreneurs’ intentions to stay or leave their residential locations.

2 Theoretical Background

The influx of self-employed in-migrants into rural areas involves multiple socio-economic dimensions, particularly related to employment generation, community dynamics, and entrepreneurial activity. Existing studies have examined these factors, providing a foundation for understanding the complex contributions these individuals make to rural development.

In terms of economic contributions, the entrepreneurial activities initiated by self-employed in-migrants significantly contribute to the economic development of rural areas. In-migrants not only fill labor market gaps in rural regions but also stimulate local economies through their consumption patterns and business ventures. In areas experiencing a high influx of new residents, evidence suggests a robust association between in-migration and entrepreneurial growth, with new businesses emerging to cater to both local and incoming populations (Kalantaridis, 2010). Migrant entrepreneurs often possess high levels of confidence and adaptability (Nguyen, 2022). In-migrants frequently bring diverse skills, enhance employment opportunities, and contribute positively to labor market dynamics (Eliasson et al., 2014). Bosworth and Atterton (2012) further emphasize that these entrepreneurs can enhance local economic ecosystems and counteract rural depopulation by introducing innovation and generating employment opportunities.

The concept of social capital is central to understanding how in-migrants integrate into rural communities and sustain their businesses. Frequent movers tend to invest less in social capital, which can negatively affect community engagement and cohesion. This highlights a potential tension, in which high rates of in-migration may dilute existing social networks in rural areas and complicate the integration of new residents into established community structures (Hotchkiss et al., 2021). Conversely, Bosworth & Atterton (2012) posit that self-employed entrepreneurs can enhance local social capital through their engagement and networking, leading to a synergistic effect where both new and existing social capital are reinforced.

Motivation for migration plays an essential role in shaping community dynamics. Stockdale (2015) describes rural in-migration as a multifaceted process, in which quality of life considerations, natural amenities, and the desire for meaningful work are often key motivators (Stockdale, 2015). Different forms of migration, whether lateral (movement between places of similar size or type, e.g., from rural area to another rural area) or counterurban (movement from more urban area to less urban or rural areas), imply varied impacts on the local labor market, entrepreneurial ecosystems, and community structures (Stockdale, 2015; Stockdale et al., 2010). These factors became particularly salient during the COVID-19 pandemic, when a surge in migration to rural areas emerged as individuals sought improved living conditions and flexibility (González-Leonardo et al., 2022). This trend emphasizes the interaction between social and environmental factors, as access to natural amenities plays a key role in attracting both in-migrants and enhancing the vitality of existing communities (Chi & Marcouiller, 2012). Chi and Marcouiller (2012) also emphasize that rural growth is closely linked to rural–urban interdependencies, where proximity to cities enhances both economic opportunity and quality of life. This correlation suggests that rural areas can benefit from wider economic growth, especially when self-employed newcomers introduce new ideas and entrepreneurial energy. Together, these factors help build a stronger and more adaptable local economy that supports job creation.

3 Methodology

3.1 Data collection and sample specification

Data from four identical regional surveys covering the North Central, Northeast, Southern, and Western Regions were used. The survey was developed as a collaborative effort led by the North Central Regional Center for Rural Development, the Southern Rural Development Center, and Auburn University. It examines key aspects of household, business, and community well-being to better understand the conditions, challenges, and opportunities faced by both rural and urban communities in the U.S.

Administered as a 20-minute questionnaire via the Qualtrics online platform, the survey covers a wide range of topics, including household demographics, income, workforce participation, entrepreneurship, caregiving, housing, broadband access, migration and staying behavior, civic engagement, community belonging, health, food security, well-being, and environmental concerns. It was intentionally designed to encourage participation from a diverse mix of households, representing different geographic areas, genders, ages, and racial and ethnic groups, to ensure balanced and inclusive representation.

Data from 18,596 households were collected in two waves. Responses from the North Central, Northeast, and Southern Regions were gathered between August and November 2024, while data from the Western Region were collected between June and August 2025, all using the Qualtrics research panel. To ensure high data quality, the survey incorporated attention-check questions and required responses

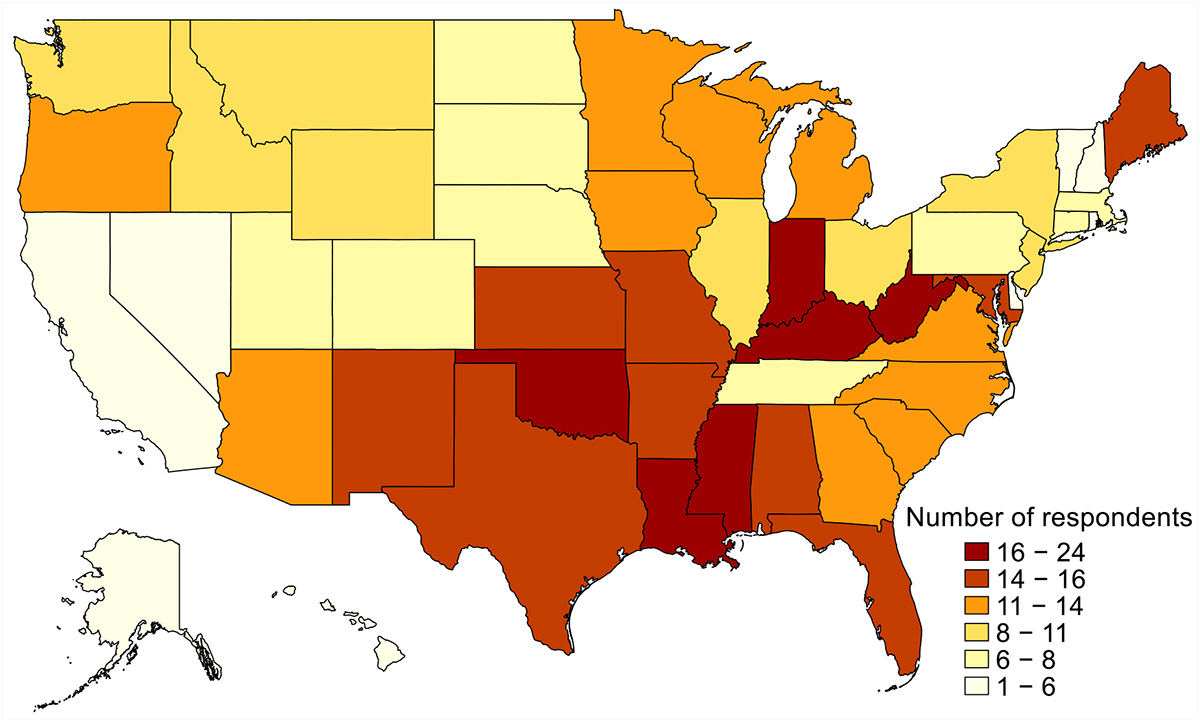

Our sample includes respondents who identified their working status as self-employed and reported living in rural areas (defined as open and/or sparsely populated countryside or towns with fewer than 5,000 people). The total number of respondents in this sample is 570. We then divided the sample into two groups: those who moved to their current residence within the past five years (in-migrants, 150 respondents) and those who had lived there for more than five years (locals, 420 respondents). Figure 1 shows the distribution of the sample by residential state.

Figure 1. Distribution of self-employed rural respondents (both in-migrants and locals) by state in the U.S. (N=570)

Source: 4R-Stat: Baseline Survey 2024 (Bednarik et al., 2025). Created by the author.

3.2 Data analysis

Similar to other studies in which respondents decide whether to migrate or stay (Garasky, 2002; Bjarnason and Thorlindsson, 2006; Thissen et al., 2010; Rerat, 2014; Clark and Maas, 2015; Bernsen et al., 2022), logistic regression analysis was employed to examine the differences in social and economic characteristics among rural self-employed in-migrants and local entrepreneurs in relation to their intention to stay. We perceived self-employed respondents’ staying in rural areas as a function of migration status (in-migrant or local), business characteristics, and respondents’ demographic characteristics.

Table 1 summarizes the definitions of the variables used in our analysis. The dependent variable, stay, captures respondents’ migration intentions, coded as 1 if they intend to stay in their current residential location within the next 12 months and 0 if they plan to move. The migration status of self-employed respondents is measured using a binary variable self_employed_inmigrant, which refers to self-employed individuals residing in the current location for five years or less and previously living outside the community (coded as 1), and self-employed individuals residing in the current location for six years or more (coded as 0). Business characteristics include indicators for industry sector (operating_in_service), having employees (employees), family business ownership (family_business), financial stability (cash_flow_problems, profitability), and community engagement measured through involvement in voluntary activities (community_engagement). Demographic controls comprise higher_education (1 = higher education, including 4-year college and higher, 0 = otherwise), gender (1 = female, 0 = male/other), and age (measured in years).

Table 1. Summary of variable definitions

| Variable Name | Question | Answer options |

| stay | Do you intend to stay in your current residential location or move somewhere else in the next 12 months? | 1=Stay; 0=Move |

| Migration status | ||

| self_employed_inmigrant | What is your employment status? [self-employed half/full-time] & How long have you been living in your current residential location? [5 years and less] & Where did you live before you moved to your current residential location? [not in the same community] | 1=Yes; 0=No |

| Business characteristics | ||

| operating_in_service | Which of the following categories best describes the industry you primarily work in (regardless of your actual position? | 1=Services

0=Otherwise |

| employees | How many employees (part-time and full-time) did the business have in 2023 (not including you)? | 1=At least one employee

0=No employees |

| family_business | Is the business a family business? | 1=Yes; 0=No |

| cash_flow_problems | How often would you say that you experienced cash flow problems in your business last year? | 1=Never

0=Otherwise |

| profitability | How profitable was your business last year? | 1=Profitable

0=Otherwise |

| community_engagement | Have you ever done any voluntary community service? | 1=Yes; 0=No |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| higher_education | What is the highest degree or level of school you have completed? | 1=Higher education 0=Otherwise |

| gender | What is your gender identity? | 1=Female

0=Male or other |

| age | What is your age in years? | Continuous |

Source: Created by authors.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the variables. Among the 570 respondents, nearly one-third were self-employed in-migrants. Approximately 76% of respondents indicated an intention to stay in their current location. The majority of businesses operated in the service sector and had at least one employee, while nearly half reported being family-owned.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of variables

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| stay | 556 | 0.761 | 0.427 | 0 | 1 |

| self_employed_inmigrant | 570 | 0.263 | 0.441 | 0 | 1 |

| operating_in_service | 558 | 0.661 | 0.474 | 0 | 1 |

| employees | 508 | 0.746 | 0.436 | 0 | 1 |

| family_business | 563 | 0.426 | 0.495 | 0 | 1 |

| community_engagement | 557 | 0.332 | 0.471 | 0 | 1 |

| profitability | 545 | 0.730 | 0.444 | 0 | 1 |

| cash_flow_problems | 535 | 0.379 | 0.486 | 0 | 1 |

| education | 566 | 0.320 | 0.467 | 0 | 1 |

| gender | 567 | 0.437 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

| age | 570 | 44.412 | 13.995 | 18 | 87 |

Source: 4R-Stat: Baseline Survey 2024 (Bednarik et al., 2025). Created by the author.

Around one-third were engaged in community activities, 73% reported their businesses were profitable, and 62% experienced cash flow problems. In terms of personal characteristics, one-third had a college education, and 44% identified as female.

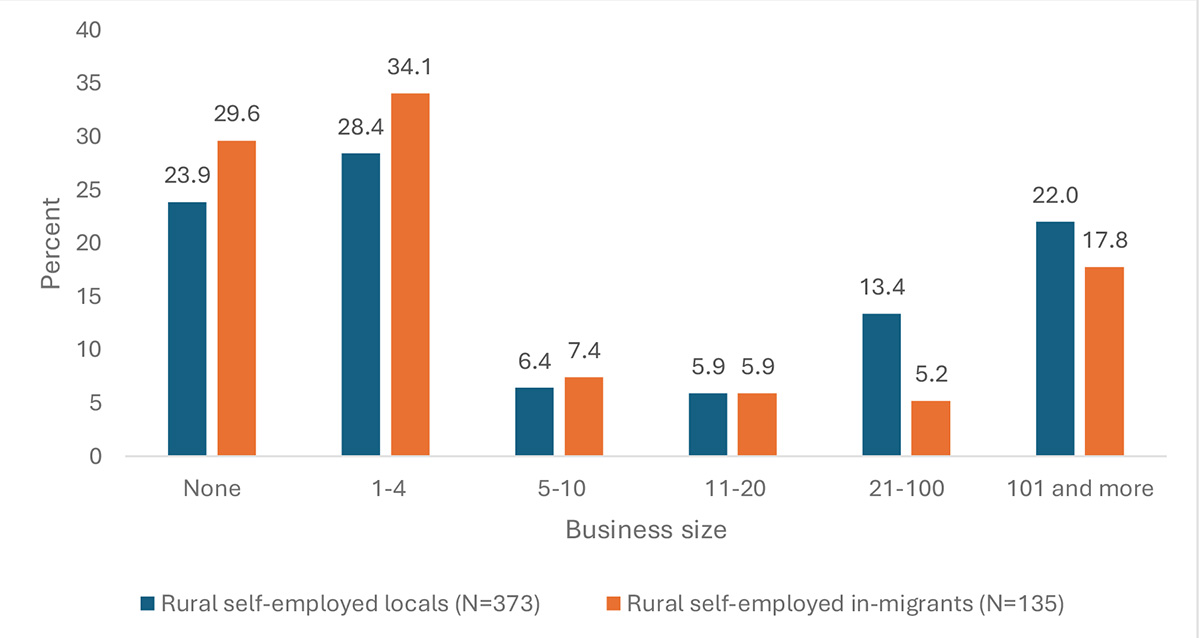

Focusing on the number of employees, Figure 2 presents the distribution of business sizes among rural self-employed individuals, comparing locals and in-migrants. In-migrants are more concentrated in the smallest business categories, with one-third operating businesses with 1–4 employees, compared to 28% of locals. Additionally, 30% of in-migrants work without employees, compared to 24% of locals. Conversely, locals are more represented in medium and large businesses: 13% of operating businesses have 21–100 employees, compared to only 5% of in-migrants, and 22% have 101 or more employees, compared to 18% of in-migrants. The mean number of employees reflects this pattern, with locals averaging 77 employees and in-migrants averaging 63 employees. In total, locals created approximately three times as many jobs as in-migrants: 28,869 and 8,493, respectively.

Figure 2. Differences in business size between rural self-employed locals and in-migrants

Source: 4R-Stat: Baseline Survey 2024 (Bednarik et al., 2025). Created by the author.

Table 3 compares the characteristics of rural self-employed locals and in-migrants. The results show that local entrepreneurs are significantly more likely to report intentions to stay in their current location and to operate family businesses than in-migrants. In contrast, self-employed in-migrants are more often engaged in service-sector activities. Profitability also differs significantly between the two groups, with locals reporting more profitable businesses than in-migrants. No significant differences are observed in the numbers of businesses with employees, cash flow problems, community engagement, education, gender, or age.

Table 3. Difference in variable characteristics between rural self-employed locals and in-migrants

| Self-employed locals | Self-employed in-migrants |

Local/ In-migrant |

|||||

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Difference |

| stay | 410 | 0.780 | 0.414 | 146 | 0.705 | 0.457 | 0.075* |

| operating_in_service | 413 | 0.637 | 0.482 | 145 | 0.731 | 0.445 | -0.094** |

| employees | 373 | 0.761 | 0.427 | 135 | 0.704 | 0.458 | 0.058 |

| family_business | 417 | 0.451 | 0.498 | 146 | 0.356 | 0.481 | 0.095** |

| community_engagement | 408 | 0.350 | 0.478 | 149 | 0.282 | 0.451 | 0.129 |

| profitability | 407 | 0.759 | 0.428 | 138 | 0.645 | 0.480 | 0.114*** |

| cash_flow_problems | 400 | 0.390 | 0.488 | 135 | 0.348 | 0.478 | 0.419 |

| education | 417 | 0.326 | 0.469 | 149 | 0.302 | 0.461 | 0.024 |

| gender | 419 | 0.446 | 0.498 | 148 | 0.412 | 0.494 | 0.034 |

| age | 420 | 44.476 | 13.946 | 150 | 44.233 | 14.176 | 0.242 |

Note: Statistical significance reported: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1. The two-sample t-test (column “Difference”) shows differences in the mean values of the variables between rural self-employed locals and in-migrants: difference = mean (rural self-employed local) – mean (rural self-employed in-migrant).

Source: 4R-Stat: Baseline Survey 2024 (Bednarik et al., 2025). Created by the author.

4 Results and Discussion

Table 4 presents results from three logistic regression models estimating the likelihood of self-employed rural respondents to stay in their current location. Model 1 includes all self-employed rural respondents, providing an overall assessment. Model 2 focuses specifically on self-employed rural in-migrants, while Model 3 examines self-employed rural locals. This approach enables comparison between in-migrants and locals, highlighting potential differences in migration status and individual, business, and demographic characteristics that influence their intention to stay.

Migration status itself is statistically significant in Model 1, indicating a negative relationship with intentions to stay. Being a self-employed in-migrant is associated with a lower likelihood of staying, suggesting that in-migrants are less likely to remain in their current rural location than the local entrepreneurs. This finding suggests that in-migrant entrepreneurs may face challenges in achieving long-term settlement and maintaining business continuity. Additionally, it aligns with prior research suggesting that mobility and uncertainty are higher among newcomers, especially those still adapting to rural environments and social networks (Hotchkiss et al., 2021). This may limit their ability to contribute to sustained job creation, as entrepreneurial benefits depend on the duration of business operation within the community.

Across all models, several consistent determinants emerge. Family business ownership increases the likelihood of staying, especially among self-employed in-migrants, where the relationship is highly statistically significant (Model 2). This finding underscores the stabilizing effect of family-based enterprises, which may embed entrepreneurs within the community and reinforce intergenerational economic ties. These results are consistent with Bosworth and Atterton (2012), who emphasize that family businesses often strengthen local resilience and contribute to the continuity of rural employment. For in-migrants, developing a family business may signal deeper integration and commitment to place, making them more likely to remain and sustain local job creation.

Having employees may reduce the likelihood of staying behavior among self-employed rural respondents. For self-employed in-migrants, the relationship is positive but statistically insignificant, indicating no meaningful association between employing others and their stay intentions. In contrast, among self-employed locals, the effect is negative and significant, showing that local entrepreneurs with employees are less likely to plan to stay. This may reflect that employing others often accompanies business growth and greater mobility, or that these entrepreneurs have more flexibility and resources to relocate.

Table 4. Results of logistic regression analysis estimating the effect of in-migration on rural labor market outcomes, with a focus on differences between rural in-migrants and locals.

| Variable |

Model 1 Self-employed rural respondents |

Model 2 Self-employed rural in-migrants |

Model 3 Self-employed rural locals |

|||

| self_employed_inmigrant | -0.615 | (0.269)** | ||||

| operating_in_service | 0.069 | (0.263) | 0.874 | (0.573) | -0.173 | (0.318) |

| employees | -0.583 | (0.311)* | 0.089 | (0.622) | -0.955 | (0.426)** |

| family_business | 0.680 | (0.264)*** | 1.493 | (0.558)*** | 0.357 | (0.319) |

| community_engagement | -0.694 | (0.256)*** | -1.219 | (0.527)** | -0.497 | (0.324) |

| profitability | -0.297 | (0.309) | -1.023 | (0.551)* | 0.028 | (0.380) |

| cash_flow_problems | 0.694 | (0.296)** | 0.733 | (0.552) | 0.646 | (0.362)* |

| education | 0.457 | (0.300) | 1.056 | (0.582)* | 0.184 | (0.375) |

| gender | 0.340 | (0.256) | 0.515 | (0.510) | 0.365 | (0.327) |

| age | 0.033 | (0.010)*** | -0.012 | (0.017) | 0.055 | (0.013)*** |

| Number of observations | 468 | 123 | 345 | |||

| Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | 0.01 | 0.000 | |||

| R2 | 0.118 | 0.166 | 0.136 | |||

Source: 4R-Stat: Baseline Survey 2024 (Bednarik et al., 2025). Created by the author.

Note: Standard errors in parentheses. Statistical significance reported *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Conversely, community engagement is associated with a negative relationship with stay intentions across models, mainly among self-employed in-migrants. This result suggests that individuals who are more socially active may also have broader networks and greater exposure to alternative opportunities, increasing their potential mobility. It also raises questions about the complexity of social capital. While engagement fosters connections, higher levels of in-migration may dilute existing social capital within a community (Hotchkiss et al., 2021), which may lead to weaker place attachment among entrepreneurial populations, particularly among self-employed in-migrants.

Not having cash flow problems is positively associated with staying behavior, particularly among self-employed locals. Profitability shows mixed and generally weak associations with staying intentions across models. It is negatively associated with staying among in-migrants, suggesting that more successful entrepreneurs may be more mobile or open to relocating to pursue new opportunities. For local self-employed individuals, the coefficient is not significant, implying that profitability plays a minimal role in their decision to stay.

Education is positively related to staying intentions only among in-migrants, implying that higher educational attainment may facilitate better adaptation, business stability, and integration into rural communities, increasing the likelihood of remaining in place. Age is another strong and consistent predictor of staying. Older entrepreneurs are significantly more likely to remain in place, suggesting that residential stability increases with life stage.

Age is a significant predictor of stay intentions among self-employed rural respondents, but its effect differs between in-migrants and natives. In Model 1, age has a positive and highly significant effect, indicating that older entrepreneurs are more likely to stay in their current rural location. This relationship remains strong and significant in Model 3, suggesting that as local self-employed individuals grow older, their attachment to place and likelihood of staying increase. This finding aligns with earlier studies (Clark & Maas, 2015; Rérat, 2014) that associate younger individuals with higher mobility and a greater openness to relocation. However, for self-employed in-migrants (Model 2), age has a small and statistically insignificant negative coefficient, implying that age does not meaningfully influence stay intentions among those who have moved into rural areas. This difference may reflect that in-migrants’ staying decisions are shaped more by other factors, such as business success, community integration, or family circumstances, than by age itself.

5 Conclusion

Staying behavior is influenced by a combination of business, financial, and personal factors, underscoring the interconnected economic and social dimensions of rural entrepreneurship.

This study shows that the contribution of self-employed in-migrants to rural job creation depends not only on their arrival but also on their ability and willingness to remain in rural areas over time. While these entrepreneurs can bring new skills, ideas, and investments, their long-term impact is realized only when they become established members of the local community. The results indicate that in-migrants are less likely to stay compared to locally rooted entrepreneurs, suggesting potential challenges in achieving long-term settlement. The findings highlight the decisive role of family businesses in fostering place attachment and residential stability, especially among in-migrants. From a policy perspective, strategies that encourage entrepreneurial in-migrants to develop family-oriented and community-embedded businesses may strengthen their attachment to place and increase the likelihood of long-term residence.

References

Bednarik, Z.; Green, J. J.; Marshall, M. I.; Russell, K. J.; Wiatt, R. D.; Wilcox Jr, M. D.; Kibria, A.; Winckel, N. (2025). 4-Region Household Data. 4R-Stat: Baseline Survey 2024 [dataset]. Purdue University Research Repository. doi:10.4231/TPH6-AJ51

Bernsen, N. R., Crandall, M. S., Leahy, J. E., Abrams, J. B., & Colocousis, C. R. (2022). Do rural youth want to stay rural? Influences on residential aspirations of youth in forest-located communities. Community Development, 53(5), 566–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2021.1998170

Bjarnason, T., & Thorlindsson, T. (2006). Should I stay or should I go? Migration expectations among youth in Icelandic fishing and farming communities. Journal of Rural Studies, 22(3), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.09.004

Bosworth, G., & Atterton, J. (2012). Entrepreneurial in-migration and neoendogenous rural development. Rural Sociology, 77(2), 254–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1549-0831.2012.00079.x

Chi, G., & Marcouiller, D. W. (2012). Natural amenities and their effects on migration along the urban–rural continuum. The Annals of Regional Science, 50(3), 861–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-012-0524-2

Clark, W. A. V., & Maas, R. (2015). Interpreting migration through the prism of reasons for moves. Population, Space and Place, 21(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1844

Eliasson, K., Westlund, H., & Johansson, M. (2014). Determinants of net migration to rural areas, and the impacts of migration on rural labour markets and self-employment in rural Sweden. European Planning Studies, 23(4), 693–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.945814

Garasky, S. (2002). Where are they going? A comparison of urban and rural youths’ locational choices after leaving the parental home. Social Science Research, 31(4), 409–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-089X(02)00007-8

González-Leonardo, M., Rowe, F., & Fresolone-Caparrós, A. (2022). [Article title not provided]. Journal of Rural Studies, 96, 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.11.006

Hotchkiss, J. L., Rupasingha, A., & Watson, T. (2021). In-migration and dilution of community social capital. International Regional Science Review, 45(1), 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017621994630

Kalantaridis, C. (2010). In-migration, entrepreneurship and rural–urban interdependencies: The case of East Cleveland, North East England. Journal of Rural Studies, 26(4), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.03.001

Nguyen, B. (2022). Internal migration and earnings: Do migrant entrepreneurs and migrant employees differ? Papers in Regional Science, 101(4), 901–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12689

Rérat, P. (2014). The selective migration of young graduates: Which of them return to their rural home region and which do not? Journal of Rural Studies, 35, 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.04.009

Stockdale, A. (2015). Contemporary and “messy” rural in-migration processes: Comparing counterurban and lateral rural migration. Population, Space and Place, 22(6), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1947

About the author:

Zuzana Bednarik, Ph.D., Research and Extension Specialist, North Central Regional Center for Rural Development

Suggested citation:

Bednarik, Z. (2026, January). What makes rural entrepreneurs stay? Social and economic characteristics of in-migrants and locals. Research Brief. North Central Regional Center for Rural Development. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.388969

[1] It should be noted here that “rural in-migration” is defined as people who moved to their current residence within the past five years. This time frame was selected for several reasons: (1) more precise information about the length of residence is not available; (2) earlier censuses (e.g., 1990, 2000) and American Community Survey questionnaires also asked about residence five years prior; and (3) using this definition allows for alignment with data from the 2020 U.S. Census. Additionally, we excluded respondents who had moved within the same community where they currently reside.